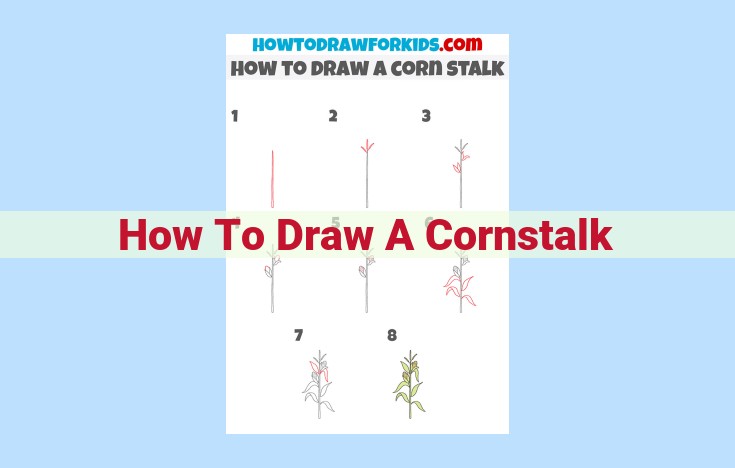

Step-By-Step Guide To Draw A Realistic Cornstalk

To draw a cornstalk, start by drawing a vertical line for the stalk. Draw short horizontal lines at regular intervals to represent the nodes. From each node, draw two or three long, pointed leaves. Add a tassel at the top of the stalk and some roots at the bottom. Shade in the leaves and add details like veins and wrinkles. Optionally, draw an ear of corn below the tassel.

The Mighty Cornstalk: A Stalwart Ally in the Realm of Nature

In the heart of agricultural fields, amidst towering stalks of corn, lies a humble yet extraordinary marvel: the cornstalk. This unassuming plant structure, often overlooked, plays a pivotal role in nourishing life and sustaining ecosystems. Its significance extends far beyond its role as a mere support for the corn’s golden ears; the cornstalk is a versatile resource with a rich history and a myriad of applications.

As the sun’s rays pierce through the canopy above, the cornstalk stands tall and erect, a testament to the enduring spirit of nature. Its sturdy stem, composed of intricate tissues, provides the necessary structural support for the plant to reach its full height and bask in the sunlight. Each node along its length marks the point where a leaf unfurls, its internode sections acting as conduits for nutrients and water to travel throughout the plant.

The cornstalk’s growth is a symphony of nature’s artistry. From its humble beginnings as a tiny seed, it embarks on a journey of transformation, passing through distinct growth stages. Each stage brings about remarkable changes, as the stalk elongates, the leaves expand, and the intricate physiological processes within reach their peak.

The Anatomy of a Cornstalk: Unveiling the Marvels of This Stalwart Plant

Every towering cornstalk stands as a testament to nature’s intricate design, its structure a symphony of specialized tissues and components. Let’s embark on a journey to dissect the anatomy of this humble yet vital plant.

The Stalk: A Sturdy Foundation

At the heart of a cornstalk lies the stalk, a sturdy pillar that anchors the plant in the soil and supports its growth. The stalk is comprised of three distinct layers:

-

Epidermis: The outermost layer, the epidermis, forms a protective barrier against environmental stresses.

-

Cortex: Beneath the epidermis lies the cortex, a spongy layer of cells that provides insulation and storage.

-

Vascular Bundles: Embedded within the cortex are vascular bundles that transport water, nutrients, and sugars throughout the plant.

Nodes: Where Growth Unfolds

Nodes are strategic points along the stalk where primary roots emerge, branching out to anchor the plant and absorb nutrients. From these nodes, leaves unfurl, capturing sunlight for photosynthesis.

Internodes: Pillars of Support

Internodes are the segments between nodes and form the bulk of the stalk. These hollow cylinders are composed of a network of sclerenchyma cells, providing rigidity and strength.

Leaves: Solar Powerhouses

Attached to the nodes, leaves are the photosynthetic powerhouses of the cornstalk. Their broad, flat blades absorb sunlight, converting it into energy for growth. The veins within the leaves, known as vascular bundles, transport water and nutrients to and from the rest of the plant.

Cornstalk Growth Stages: A Journey from Seed to Maturity

The life cycle of a cornstalk is a captivating tale that unfolds in distinct stages, each marked by remarkable transformations that lay the foundation for its towering presence in the field. From its humble beginnings as a tiny seed to its majestic stature as a tall, sturdy stalk, the cornstalk embarks on an intricate journey of growth and development.

Germination: The Birth of a Plant

The journey begins with a seed, a tiny vessel that holds the dormant potential for life. When conditions are right, the seed imbibes water, triggering a cascade of biochemical reactions that awaken the embryo within. The radicle, the first root, emerges, anchoring the seedling in the soil, while the coleoptile, a protective sheath, shields the first true leaves as they unfurl towards the sunlight.

Vegetative Growth: Establishing the Base

As the seedling establishes its foothold, it enters a period of rapid vegetative growth. The nodes, swollen areas on the stalk, become apparent as the plant gains height. Internodes, the elongated sections between nodes, contribute to the stalk’s overall length. The leaves, true photosynthetic powerhouses, unfurl in a spiraling pattern, capturing sunlight to fuel the plant’s growth.

Reproductive Phase: The Culmination of Growth

The vegetative growth phase culminates in the reproductive phase, when the cornstalk transitions from leaf production to reproduction. Tassels, the male flowering structures, emerge at the top of the stalk, releasing pollen. The silks, long, delicate strands emerging from the ears, receive the pollen, allowing fertilization to occur.

Grain Filling: The Reward for Growth

After fertilization, the fertilized kernels begin to develop and mature within the ears. The stalks continue to elongate, providing support for the developing grains. The leaves remain photosynthetically active, contributing to the grain filling process.

Maturity: Reaching Full Potential

As the kernels reach their full size, the stalk transitions to maturity. The leaves senesce, turning yellow and brown, as their nutrients are translocated to the developing kernels. The stalk becomes stiff and dry, providing structural support for the heavy ears.

The Legacy of the Cornstalk

With the harvest, the cornstalk’s journey comes to an end. Yet, its legacy lives on in the nutritious kernels it produces, the materials it provides for construction and biofuel, and the profound impact it has on ecosystems and human well-being.

Cornstalk Varieties: A Comprehensive Overview

The cornstalk, an integral component of the maize plant, exhibits remarkable diversity across different varieties. Each variety possesses distinctive characteristics and serves specific purposes, influenced by factors like climate, soil type, and intended use.

Stalk Height and Strength:

Cornstalk varieties range widely in height, from dwarf varieties standing around 3 feet tall to giant varieties towering over 15 feet. Taller stalks are often preferred for forage production, while shorter stalks are suitable for grain or silage purposes. The stalk’s strength is crucial for supporting the heavy ears of corn, especially in areas prone to strong winds.

Leaf Type and Angle:

Leaves of cornstalks vary in shape, size, and angle of attachment. Varieties with upright leaves allow for denser planting, maximizing light interception for photosynthesis. Conversely, varieties with drooping leaves provide more shade to the ground, suppressing weed growth.

Days to Maturity:

The number of days from planting to maturity is a key consideration for farmers. Early-maturing varieties reach maturity in as little as 80 days, allowing for multiple harvests in a single growing season. Late-maturing varieties, on the other hand, require a longer growing period but generally yield higher grain production.

Corn Hybrids and Genetic Modifications:

Modern corn breeding programs have resulted in corn hybrids with improved traits such as disease resistance, drought tolerance, and increased grain yield. Genetically modified cornstalks can incorporate specific genes to enhance nutritional value, resistance to pests, or herbicide tolerance.

Factors Influencing Cornstalk Variety Selection:

The selection of cornstalk variety depends on a combination of factors, including:

- Intended use: Grain production, forage, silage, or biofuel.

- Climate: Temperature, rainfall, and frost dates.

- Soil type: Fertility, drainage, and acidity.

- Production system: Conventional, organic, or no-till farming.

- Farmer preferences: Maturity time, ease of management, and yield potential.

By selecting the most suitable cornstalk variety for their specific conditions, farmers can optimize crop performance and maximize their returns.

Cornstalks: Beyond the Cob

Cornstalks, the often-overlooked stalks of our beloved corn, hold a wealth of versatile uses that extend far beyond their familiar place as a livestock feed.

Animal Feed: The Nutritious Backbone

Cornstalks serve as a cost-effective and nutritious source of forage for livestock. Their high fiber content aids in digestion, while their low protein levels make them an ideal supplement to diets rich in protein-rich feedstuffs.

Biofuel: The Powerhouse of Sustainability

The fibrous nature of cornstalks makes them a promising feedstock for the production of renewable biofuels. By converting cornstalks into ethanol or biogas, we can reduce our dependence on fossil fuels and mitigate the environmental impact of energy production.

Construction Materials: The Structural Gem

Cornstalks are also versatile construction materials. Baled cornstalks provide insulation and moisture resistance in building insulation, while the stalks’ strong fibers can be used in composite building materials and particleboard. This not only reduces the environmental impact of construction but also provides a cost-effective alternative to traditional materials.

Economic and Environmental Benefits: A Win-Win

The economic benefits of cornstalk utilization are substantial. By utilizing cornstalks as animal feed, biofuel, and construction materials, farmers and businesses can increase their revenue streams and reduce waste. Additionally, the use of cornstalks in these applications reduces greenhouse gas emissions and promotes sustainable land management.

Hence, the humble cornstalk, often seen as a by-product, emerges as a multifaceted resource with the potential to transform industries, nourish animals, and protect our environment. Through innovative applications, we can unlock the full potential of this remarkable plant, ensuring a sustainable future for generations to come.

Cornstalk-Related Terms: Unraveling the Cornstalk’s Anatomy and Physiology

To delve into the intricate world of cornstalks, familiarizing ourselves with some key terms is essential. These terms provide a solid foundation for understanding the cornstalk’s anatomy and physiology.

Node: The node, an important juncture in the cornstalk, is where the leaf sheath and blade attach to the stalk. This strategic location serves as a growth point for new branches, known as tillers.

Internode: Connecting the nodes, internodes are the elongated segments of the stalk. They consist of sturdy tissues that provide structural support and facilitate the transport of water and nutrients throughout the plant.

Tiller: A tiller is a secondary stalk that emerges from the base of the main stalk, often at the nodes. Tillers contribute significantly to the plant’s overall biomass and yield.

Comprehending these terms empowers us to appreciate the remarkable complexity of the cornstalk’s architecture. The node, internode, and tiller work in harmony to ensure the plant’s growth, stability, and productivity.